Spoiling Your Milk: Clever Dairy Tech

Some of the most interesting technologies I’ve encountered are also among the simplest. As I was looking over the topics I covered years ago on my old website Interesting Thing of the Day, I noticed a surprising number involving dairy products. I’d like to share (or re-share) three of those with you here. Because I don’t just take care of my milk—I spoil it!

French Butter Dishes

The equation is simple enough for a child to understand, and yet most restaurants apparently don’t grasp it:

cold butter + soft bread = sadness

The civilized world has seemingly decided that refrigeration is the only possible way to keep butter fresh, and that, moreover, letting butter warm to room temperature before serving is unthinkably complicated. And thus we replace one problem (spoiled butter) with another (spoiled bread).

Sometimes lower-tech solutions are more elegant and effective. In the case of butter, refrigeration is one way to inhibit the growth of microorganisms. Another is to deprive them of oxygen. You can do this very easily with a couple of pieces of ceramic and a little bit of water.

A French butter dish (more on that name in a moment) consists of two parts: a smaller container that holds butter, and a larger container that holds water. You simply flip over the part with the butter and set it in the part with the water, and presto! You get an airtight seal that keeps your butter fresh without refrigeration. And, because the butter is mostly fat, it won’t dissolve into the water. Your butter can stay at room temperature all the time (so it’s soft enough to spread) while remaining fresh.

Although this design originated in the French town of Vallauris, I don’t think I saw even one of them during the five years I lived in France, and it’s certainly not what most French people would think of when they hear “butter dish.” This design is much more popular in North America, where the best-known brand is the Butter Bell, made by L. Tremain, Inc. You can find butter bells and many other similarly designed butter crocks on Amazon.com.

The Girolle

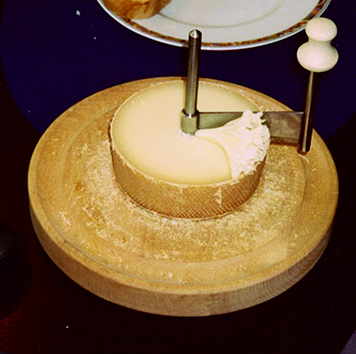

Back in 2004 when I wrote about the Girolle on Interesting Thing of the Day, this device had barely registered on the North American radar. Times have changed, and I’ve seen them in a number of American stores (albeit usually with other names). So this might not be news to you, but that’s OK. It’s still pretty neat: it’s a simple tool for shaving cheese into flower shapes called rosettes.

A Girolle is basically a metal spindle on a wooden base, with a rotating blade attached to the spindle at a 90° angle. As you turn the handle, the blade shaves off a thin layer of cheese, which crinkles around the edges and turns into a lovely, edible ornament. It won’t work with just any cheese, though. The cheese must have the right size, shape, and texture—not too hard, not too soft. The very best cheese to pair with a Girolle is called Tête de Moine, or “Monk’s Head” cheese, a stinky and somewhat expensive cheese that comes from the same region of Switzerland as the Girolle. In fact, that was the cheese that inspired the invention.

You may be thinking that the Girolle was a solution in search of a problem; after all, no one needs shaved cheese, right? There’s no essential difficulty in slicing and eating Tête de Moine cheese in the conventional way. But for hundreds of years, shaving Tête de Moine into rosettes was the local custom, and it was a real pain to do manually. The Girolle’s inventor, Nicolas Croiviser, was in fact trying to make the process less labor-intensive, especially for large quantities of cheese. And his obvious-in-retrospect design did exactly that.

Milk in a Box

If you go to a French supermarket to buy milk, don’t look in the refrigerated aisle. The milk, packaged in either boxes or plastic bottles, will be on shelves with the soft drinks and water. (Well, you might find a few refrigerated varieties too, but certainly the bulk of the milk won’t be.) In France, as in many parts of the world, milk is transported, stocked, sold, and stored at room temperature—and it’s done safely because of the special manner of pasteurizing and packaging it.

Regular pasteurization kills most but not all microorganisms in milk by heating it to about 140°F (60°C) for a half hour, or to 163°F (73°C) for about 15 seconds. That gives milk a shelf life of a week or more (assuming it’s refrigerated and covered), while affecting the taste only slightly.

Ultra High Temperature (or UHT) pasteurization changes the equation, heating the milk to a higher temperature (about 275°F, or 135°C) for only two seconds and then rapidly cooling it. That higher temperature kills nearly all the microorganisms. If the milk is then transferred, in a sterile environment, to aseptic packaging (such as the boxes we North Americans commonly associate with fruit juice), it’ll remain fresh for six to nine months.

Although early forms of UHT altered milk’s flavor in ways many people found unsatisfactory, technology and taste have improved significantly over time. I couldn’t discern anything unusual about the taste of the UHT milk I bought in France (which I always refrigerated before drinking). And I thought it was fantastic that I could stock milk in my pantry along with other nonperishable goods, and not have to buy it every few days.

It’s difficult to find UHT milk in the United States. Americans are used to buying refrigerated milk, and I think the typical American consumer would find milk in a box even more suspicious than wine in a box. Because there’s very little demand for it here, UHT milk costs more than regular milk in the United States, even though it’s less expensive to deliver and store. In parts of Europe where UHT milk is the default, you don’t have the same price issues.

But then, it took texting a long time to catch on in the United States too. In the late 1990s, a Swiss friend asked me why Americans hardly ever used SMS, which by then was already commonplace in Europe. And just look at us now. So maybe there’s still hope for milk in a box to become popular in America.